A ‘quantum processor’ has solved a physics problem on the behaviour of magnetism in certain solids that would take the largest conventional supercomputers hundreds of thousands of years to calculate. The result is the latest claim of a machine showing ‘quantum advantage’ over classical computers.

Although Google, headquartered in Mountain View, California, and others have claimed to have achieved quantum advantage — most recently with the Sycamore chip that Google unveiled in December — researchers at D-Wave, a company in Palo Alto, California, say that their result, published in Science1, is the first that solves an actual physics question. “We believe it’s the first time anyone has done it on a problem of scientific interest,” says D-Wave physicist Andrew King.

The team did great work — but classical computing should not be counted out quite yet, says Miles Stoudenmire, a researcher at the Flatiron Institute Center for Computational Quantum Physics in New York City. “We’re still in the race.”

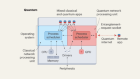

The result also validates the approach that the company has taken to quantum computing, King says. Rather than building a ‘universal’ quantum computer — one that could run any quantum algorithm — D-Wave has limited its approach to performing certain calculations, which is easier to scale.

An early pioneer in the quantum field, D-Wave machines have long led the industry in terms of number of qubits, the quantum equivalent of classical bits of information. The latest processor has thousands of qubits. “These are results of 25 years of hardware development and research at D-Wave,” says Mohammad Amin, a physicist at the company.

Magnetic problem

The problem solved by D-Wave concerns the theory of magnetism, a large field of theoretical physics. The electron spins of each atom act like magnetic needles, and the way they orient themselves inside a solid in response to their neighbours’ orientations has long provided a prototype for the study of complex systems.

In a typical permanent magnet, the spins all align in the same direction. But in general materials, neighbouring spins have conflicting influences on each other, and stable arrangements either don’t exist or are extremely difficult to predict. Quantum effects add complications.

King, Amin and their collaborators at D-Wave and several academic laboratories used the latest D-Wave machine, called Advantage2, to simulate the arrangements of spins in several 3D crystal structures. They studied a specific problem in which the temperature of the material starts at absolute zero, and quantum fluctuations let it transition from one state to another. They estimate that their machine achieved the result exponentially faster than any classical calculation could.

Advantage claims challenged

The result follows several claims of quantum advantage. Google made the first claim of a quantum advantage in a paper that caused a sensation in 20192. It used a fully programmable, or universal, quantum computer with superconducting qubits to perform a calculation that was designed to test for quantum advantage but had no practical application. Soon, IBM, headquartered in Armonk, New York, and other companies showed that by improving classical techniques, they could still run the same calculations on ordinary computers.

IBM then achieved3 a quantum advantage on a useful application in 2023. But last year, that claim suffered a similar fate to Google’s4: Stoudenmire and his collaborators showed their classical algorithms could solve the problem as quickly.

‘A truly remarkable breakthrough’: Google’s new quantum chip achieves accuracy milestone

‘A truly remarkable breakthrough’: Google’s new quantum chip achieves accuracy milestone

IBM quantum computer passes calculation milestone

IBM quantum computer passes calculation milestone